Liberate Your Lawn & Garden: Act Now to Replace Any of Virus-like Invasive Plants

It’s mid-March and the whole family is unexpectedly home! In this time of social distancing, I’m grateful for the Wissahickon and a new opportunity to experience the incredible transformation of spring.

As Mother Earth begins to wake, unfold and stretch, it’s also a great time of year to identify plants. The early risers are early indeed this year. Look up and you can see a flush of red in the treetops, as the flowers of red maple (Acer rubrum) open. We also can easily identify the swelling globular yellow flower buds of Spicebush (Lindera benzoin), an understory shrub that gets its name from its fragrant twigs, leaves and flowers.

While this makes me smile, it’s also easy to identify some of the most invasive species impacting the Wissahickon. The green and yellow carpet of lesser celandine (Ranunculus ficaria), and the chartreuse emerging leaves of winged euonymus or burning bush (Euonymus alatus) are beautiful but deceiving. Like a virus, these species spread with gusto and negatively impact the health and ecology of the park.

Lesser celandine and burning bush are both listed as invasives by the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. They are early risers with little to no natural predator or disease control. Both are bullies that form dense plant colonies and shade that effectively blocks out native ephemerals such as bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis), wild ginger (Asarum canadense), spring beauty (Claytonia virginica), twinleaf (Jeffersonia diphylla), squirrel-corn (Dicentra canadensis), trout lily (Erythronium umbilicatum), trilliums (Trillium spp.) and Virginia bluebells (Mertensia virginica).

These are all beautiful woodland ground covers that provide critical early nectar and pollen for native bees and seeds and fruit for wildlife. Sadly, lesser celandine is finding its way into our gardens uninvited, while burning bush, a nursery industry top seller, continues to fly off the shelves.

What should you do to control the spread? First, don’t buy them. Second, remove them. The best way to control lesser celandine is to pull it out now before it goes to seed. Be sure to get the root tubers, because if left in the ground, It. Will. Come. Back. Also, be sure to discard it, not compost it.

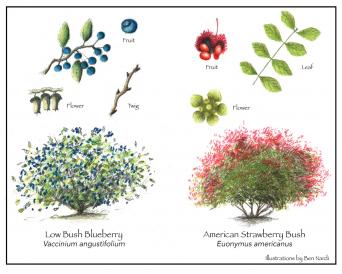

If your neighborhood is like mine, you may have a 30 to 40, year-old burning bush shrub that arches over your entryway or decorates your foundation. Cut them down, and plant American strawberry bush (E.americanus) or low bush blueberry (v.augustfolium), both stunning local native alternatives. If you like to hike around Toleration Statue, you have walked by both.

Low bush blueberry grows 12-24 inches tall on moist, well-drained slopes. Too much water and the roots will rot. It grows in both sun and shade; however, in shade the blue edible fruits my family likes to hunt for and eat are limited. American strawberry bush is a taller understory suckering shrub (4-6 feet high) that thrives in moist, organically rich soil in woodland shade. Its red, strawberry-like fruit opens in fall, revealing beautiful reddish orange seeds that provide food for birds and wildlife. Its foliage may not be as brilliant as the bush blueberry, but the bright green stems of American strawberry provide winter and spring seasonal interest.

As we take precautions to protect our health and wellness, I encourage you also to look at how you can help protect our local forest in your garden. Please consider any or all of the native alternatives listed above.

Sarah Endriss is the owner of Asarum LandDesign Group, a woman-owned firm specializing in ecological planning and landscape design.